PART 1) Pre-Apartheid (1886-1948) to Apartheid (1950s-1994)

1.01 Early Settlement, 1886-1900s

What generated Johannesburg’s early urbanism was gold (greed).

Johannesburg is the result of private enterprise. The city evolved from the pursuit for fortune. Pure and simple.

The high plateau on which Johannesburg was built was originally an arid plateau inhabited by a few Boer farmers grazing cattle and cultivating maize and wheat. This harsh and isolated landscape was transformed after the discovery of gold in 1886. An Australian prospector, George Harrison, discovered Main Reef in March of 1886. Within weeks hordes of prospectors and fortune hunters began to arrive and officials of Pretoria government were quickly sent to inspect the diggings and to lay out plan for a town.

Johannesburg expanded at a phenomenal rate and within 3 years had become the largest town in South Africa. The gold rush attracted people from all over the world; Johannesburg became a cosmopolitan town where vast fortunes could be made overnight. Gambling dens, brothels and riotous canteens lined the streets and hundreds of ox-drawn wagons arrived daily to deliver food, drink and building supplies. Johannesburg was populated with 75,000 white residents and many more Africans by the turn of the century.

The city is in lack of pretence to anything but the quest for money.

1.02 Foundation of Segregation Urbanism, 1886-1950

Mining industry as pioneer of apartheid

The mineral discoveries fundamentally altered South African society. It was at the mines that many of the features that dominated life in 20th century South Africa first came into existence- in particular the pass laws, the migrant labour system, the compounds and the colour bar.

Exploitation of Labour: Pass Laws and Migrant Labour System

The government was unwilling to institute too overtly racist legislation, but they did introduce a pass law that required all African present in the town to carry a pass signed either by a magistrate or a mine owner showing that they had legitimate employment. This legislation was aimed at preventing large numbers of Africans arriving at the mine in hope of jobs and hence pushing down wage rates. To keep the wage as low as possible and to substitute more expensive white labour with cheaper African labour the migrant labour system was introduced. Only male African labour could come to the mines. Families were left at home on the reserves.

Urban Planning Device: Townships

From 1923-27 a series of laws were passed confining Africans to specially demarcated residential areas. By the mid-1930s several ‘townships’ had been built where modern Soweto sprawls today. By 1933 the whole of Johannesburg was proclaimed white, and by 1938 the bulk of the black population had been moved south. The only black spot in the white landscape to the north was the freehold township of Alexandra about twenty kilometres north of the city centre.

Architectural Device: Compound

All African labour had to live in a single compound above the mine from which they were prohibited to leave for the duration of their contract. The official reason was that this was to prevent diamond thefts, but there were many other advantages for the employers. As for compounds were only to house single male African labourers the company did not have to pay adequate wages to support the miner’s family, who usually remained in the reserves and farmed to meet their own subsistence needs. Furthermore the mine owners could be assured of economies of scales in buying in provisions and, therefore were able to feed African labourers on the site. If African had to buy their own food they would have required higher wages.

Opportunity Reservation System: Colour Bar

The agreement between white labour and capitalists was that in exchange for the political support of labour the capitalists would introduce a colour bar that reserved more skilled and better-paid jobs for whites only.

Identity Problem Stemmed Apartheid

During early decades of 20th century many poorer Afrikaner migrated to the new towns in search of work, with few skills to offer, they often ended up poor and unemployed. Their plight, labelled ‘the poor white problem’ was a continual worry for Afrikaner politicians. They feared that their marginal position in the new towns was pushing them into closer contact with the growing band of African urban poor. The ‘poor white problem’ was a key motivation behind the deepening of segregationist policies, designed to keep black and white apart in order to maintain Afrikaner identity.

Fear Induced Apartheid

The economic boom caused by the war led to massive African urban migration and the National Party (a united party of British and Afrikaners) used this to stir up fear amongst white, especially Afrikaner, votes. In 1948 they voted on an election platform promising a new ideology of apartheid. However, apartheid was by no means an exclusively Afrikaner ideology.

The fear was felt over a century and a half by Afrikaans-speaking descendents of the Voortrekkers for those they had conquered by means of horse and gun. At the back of the Boer mind laid the very fear that one day the conquered, who vastly outnumbered the conquerors, would rise. The only way to prevent this was to keep the conquered under the iron heel from the beginning. Apartheid is a deliberate philosophy of oppression.

The Afrikaners, in an attempt to justify their oppressive rule, adopted a stern Calvinist brand of Christianity, which successfully rolled their political and religious creeds into one: South Africa was their promised land and by the promise the subjugation of blacks was perceived as a necessary part of the divine scheme of bringing Christianity and ‘civilisation’ to the unenlightened.

Twist of Darwinism

There was a distinct group of white South Africans who were very concerned about the plight of Africans and saw the solution as being total separation of the two races. They believed that rapid urbanisation was destroying the basis of African culture and that they needed to be protected from the evils of white urban civilisation. This ideology was tied up with ideas of both paternalism, that white should be like parents to child-like Africans, and the ideas of Social Darwinism, that different races were at different points along an evolutionary scale.

These ideas were considered by a group of Afrikaner intellectuals who saw the total separation of the races as being the only way in which whites could maintain political power over South Africa. Later apartheid became in essence a way of ensuring a continual supply of cheap African labour whilst denying African any political rights.

1.03 The Operation of Apartheid, 1950s

1950, Group Areas Act

Under the Group Areas Act different areas of each city were reserved for one of the four major population groups (white, Indian, Coloured or African). Before the passing of this law, most cities and towns were already segregated to an extent. The government attempted to consolidate this pattern of segregation into bigger, clearly defined blocks of land and to do away with any areas where there was a mixture of different races. This process continued right through to the mid-1980s.

Evacuation

Prior to the Group Area Act much of the poorer urban population lived in slums near the central business areas of industrial centres. These areas were home to large numbers of Africans, Indians and Coloured and a few poor whites. Under this law, these slum areas were knocked down and new housing for whites was built in the place. The African, Indian and Coloured populations were moved to new, racially segregated, planned settlements on the outskirts of cities, known as townships.

Strategy in Urban Control

Townships are some distance from the city centre and are divided from the white suburbs by areas of unoccupied land/buffer zone.

There are usually only one or two access routes into the township and the streets are wide and straight: both were deliberately intended to make the control of unrest and protest easier to handle. The best known of these township areas is the vast residential area of Soweto (South Western Townships). These townships contrast sharply with the suburbs reserved for white populations during the apartheid years. And people did not live in Soweto by choice.

1.01 Early Settlement, 1886-1900s

What generated Johannesburg’s early urbanism was gold (greed).

Johannesburg is the result of private enterprise. The city evolved from the pursuit for fortune. Pure and simple.

The high plateau on which Johannesburg was built was originally an arid plateau inhabited by a few Boer farmers grazing cattle and cultivating maize and wheat. This harsh and isolated landscape was transformed after the discovery of gold in 1886. An Australian prospector, George Harrison, discovered Main Reef in March of 1886. Within weeks hordes of prospectors and fortune hunters began to arrive and officials of Pretoria government were quickly sent to inspect the diggings and to lay out plan for a town.

Johannesburg expanded at a phenomenal rate and within 3 years had become the largest town in South Africa. The gold rush attracted people from all over the world; Johannesburg became a cosmopolitan town where vast fortunes could be made overnight. Gambling dens, brothels and riotous canteens lined the streets and hundreds of ox-drawn wagons arrived daily to deliver food, drink and building supplies. Johannesburg was populated with 75,000 white residents and many more Africans by the turn of the century.

The city is in lack of pretence to anything but the quest for money.

1.02 Foundation of Segregation Urbanism, 1886-1950

Mining industry as pioneer of apartheid

The mineral discoveries fundamentally altered South African society. It was at the mines that many of the features that dominated life in 20th century South Africa first came into existence- in particular the pass laws, the migrant labour system, the compounds and the colour bar.

Exploitation of Labour: Pass Laws and Migrant Labour System

The government was unwilling to institute too overtly racist legislation, but they did introduce a pass law that required all African present in the town to carry a pass signed either by a magistrate or a mine owner showing that they had legitimate employment. This legislation was aimed at preventing large numbers of Africans arriving at the mine in hope of jobs and hence pushing down wage rates. To keep the wage as low as possible and to substitute more expensive white labour with cheaper African labour the migrant labour system was introduced. Only male African labour could come to the mines. Families were left at home on the reserves.

Urban Planning Device: Townships

From 1923-27 a series of laws were passed confining Africans to specially demarcated residential areas. By the mid-1930s several ‘townships’ had been built where modern Soweto sprawls today. By 1933 the whole of Johannesburg was proclaimed white, and by 1938 the bulk of the black population had been moved south. The only black spot in the white landscape to the north was the freehold township of Alexandra about twenty kilometres north of the city centre.

Architectural Device: Compound

All African labour had to live in a single compound above the mine from which they were prohibited to leave for the duration of their contract. The official reason was that this was to prevent diamond thefts, but there were many other advantages for the employers. As for compounds were only to house single male African labourers the company did not have to pay adequate wages to support the miner’s family, who usually remained in the reserves and farmed to meet their own subsistence needs. Furthermore the mine owners could be assured of economies of scales in buying in provisions and, therefore were able to feed African labourers on the site. If African had to buy their own food they would have required higher wages.

Opportunity Reservation System: Colour Bar

The agreement between white labour and capitalists was that in exchange for the political support of labour the capitalists would introduce a colour bar that reserved more skilled and better-paid jobs for whites only.

Identity Problem Stemmed Apartheid

During early decades of 20th century many poorer Afrikaner migrated to the new towns in search of work, with few skills to offer, they often ended up poor and unemployed. Their plight, labelled ‘the poor white problem’ was a continual worry for Afrikaner politicians. They feared that their marginal position in the new towns was pushing them into closer contact with the growing band of African urban poor. The ‘poor white problem’ was a key motivation behind the deepening of segregationist policies, designed to keep black and white apart in order to maintain Afrikaner identity.

Fear Induced Apartheid

The economic boom caused by the war led to massive African urban migration and the National Party (a united party of British and Afrikaners) used this to stir up fear amongst white, especially Afrikaner, votes. In 1948 they voted on an election platform promising a new ideology of apartheid. However, apartheid was by no means an exclusively Afrikaner ideology.

The fear was felt over a century and a half by Afrikaans-speaking descendents of the Voortrekkers for those they had conquered by means of horse and gun. At the back of the Boer mind laid the very fear that one day the conquered, who vastly outnumbered the conquerors, would rise. The only way to prevent this was to keep the conquered under the iron heel from the beginning. Apartheid is a deliberate philosophy of oppression.

The Afrikaners, in an attempt to justify their oppressive rule, adopted a stern Calvinist brand of Christianity, which successfully rolled their political and religious creeds into one: South Africa was their promised land and by the promise the subjugation of blacks was perceived as a necessary part of the divine scheme of bringing Christianity and ‘civilisation’ to the unenlightened.

Twist of Darwinism

There was a distinct group of white South Africans who were very concerned about the plight of Africans and saw the solution as being total separation of the two races. They believed that rapid urbanisation was destroying the basis of African culture and that they needed to be protected from the evils of white urban civilisation. This ideology was tied up with ideas of both paternalism, that white should be like parents to child-like Africans, and the ideas of Social Darwinism, that different races were at different points along an evolutionary scale.

These ideas were considered by a group of Afrikaner intellectuals who saw the total separation of the races as being the only way in which whites could maintain political power over South Africa. Later apartheid became in essence a way of ensuring a continual supply of cheap African labour whilst denying African any political rights.

1.03 The Operation of Apartheid, 1950s

1950, Group Areas Act

Under the Group Areas Act different areas of each city were reserved for one of the four major population groups (white, Indian, Coloured or African). Before the passing of this law, most cities and towns were already segregated to an extent. The government attempted to consolidate this pattern of segregation into bigger, clearly defined blocks of land and to do away with any areas where there was a mixture of different races. This process continued right through to the mid-1980s.

Evacuation

Prior to the Group Area Act much of the poorer urban population lived in slums near the central business areas of industrial centres. These areas were home to large numbers of Africans, Indians and Coloured and a few poor whites. Under this law, these slum areas were knocked down and new housing for whites was built in the place. The African, Indian and Coloured populations were moved to new, racially segregated, planned settlements on the outskirts of cities, known as townships.

Strategy in Urban Control

Townships are some distance from the city centre and are divided from the white suburbs by areas of unoccupied land/buffer zone.

There are usually only one or two access routes into the township and the streets are wide and straight: both were deliberately intended to make the control of unrest and protest easier to handle. The best known of these township areas is the vast residential area of Soweto (South Western Townships). These townships contrast sharply with the suburbs reserved for white populations during the apartheid years. And people did not live in Soweto by choice.

1.04 History of Violence, 1886-1960s

Raw City, 1886

Johannesburg grew up a violent, hard-drinking town servicing tens of thousands of African labourers, skilled white machine operators and entrepreneurs. With very few females, prostitution became the most lucrative industry after mining. Europeans working class girls were cheated and lured to come to Johannesburg and were kept in the brothels as sex slaves. In the early 1890’s a few suburbs, like Parktown and Houghton (5 minutes drive from downtown), had appeared for mining magnates and their families, but the squalid city remained an anarchic place governed by money, greed and raw energy.

Non-violence Campaign

In late 1959 PAC (Pan African Congress, rightist African organization) launched a massive anti-pass law campaign. The pass laws were one of the most hated apartheid policies as they strictly controlled African mobility and were also used by the police as an excuse to stop and search any African.

Their campaign started on 21 March 1960 called on all African men to leave their passes at home and present themselves for arrest at the nearest police station. They believed that the prison could be swamped and the pass laws would have to be revoked. This led to police’s opening fire in Sharpville. Most of the 69 dead and 180 wounded were shot in the back.

As news spread around the country, Africans rioted, went on strike and in Cape Town marched into the city centre. This caused panic amongst the white residents and police. A nationwide state of emergency was declared and the police arrested thousands of political activists from across the country. Strikers were beaten and township food supplies cut off to force people back to work. Both ANC (African National Congress) and PAC were banned. Many of their leaders imprisoned without being charged. Over the next few months the unprecedented harshness of the police action broke the back of the widespread resistance. It also convinced many ANC and PAC members that non-violence action meant nothing if it was met by police brutality.

Armed Attack

ANC established an organised armed wing to carry out sabotage attacks on economic targets, and not to threaten human lives. During an 18 months period from December 1961, 200 attacks were carried out. The activists did attack policemen and collaborators. Its headquarter was discovered at Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia. Majority of its leadership, including Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki, were arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment.

1.05 History of Violence, 1970s

Continuation of Twisted Darwinism and its Paradox

Forced removal increased as the government set about dividing the country into clear white, Indian, Coloured and African zones. Africans living in cities like Pretoria with ‘homeland’ areas within daily commuting distance (in reality huge distances) found themselves removed to new townships within the ‘homeland’. On occasions the government also altered the borders of ‘homeland’ so that townships on the outskirts of cities were absorbed into a new administrative structure. Forced removals and natural population growth meant that the populations of the ‘homeland’ increased rapidly and though these areas were officially rural their densities were closer to urban areas. All Africans were supposed to express their political rights through the ‘homeland’ administration. During 1970s the South African government encouraged the ‘homeland’ administrations to become independent states. Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana and Venda’s independence were only recognised by South Africa. They do not even recognise one another’s independence.

Bophuthatswana took advantage of its separate status to open casinos- at the time forbidden in South Africa. Sun City, the first large hotel/casino complex, was such a success that it inspired all the other ‘homeland’ governments, as well as those of Lesotho and Swaziland, to open similar enterprises. Sun City is an interesting example of contrast between rich and poor; the gambling rooms and one-armed-bandits operate night and day, while outside the perimeter fence many local Tswana live in terrible poverty. Sun City was upstaged by the even larger Lost City- a transcended Grand Kitsch complex that claims to recreate the atmosphere of King Solomon’s Mines.

Opposition against Oppression

From 1973 on, the Trade Unions, instead of political groups, led successful strikes demanding increased wages. Their strategy was to refuse electing leaders so that the employer had no target and the police could not be called in to arrest strike leaders.

The early 1970s also saw the rise of a more vocal African student protest movement, led by the South Africa Students Organisation (SASO). They rebelled against the mental oppression that taught them white people were somehow innately superior to blacks and an education system designed to make them fit only for un- and semi-skilled occupations. They protested the enforcement of Afrikaans language as a medium of instruction. On the 16 June 1976 a Soweto school pupils’ committee organised a peaceful march, which met with a violent response. The protest ended up as a rampage destroying every symbol of their oppression they could get to, including the government-run beer halls which many pupils felt brought off their fathers’ opposition to state oppression with cheap beer. This event is Soweto Uprising.

The ANC used this new climate of opposition to re-infiltrate South Africa. In the late 1970s they began a new campaign of sabotage with less care to avoid civilian casualties. The ANC released a statement that they were at war with the apartheid state.

1.06 A Vicious Island, 1970s- 1980s

The ANC in exile managed to foster anti-apartheid groups in Europe and North America to put pressure on their governments to institute economic sanctions against South Africa. Most Commonwealth governments supported these sanctions and also instituted sporting and cultural sanctions. This international isolation of Pretoria added to their gradual geopolitical isolation in southern Africa during the 1970s.

The independence of Angola and Mozambique in 1976 and Zimbabwe in 1980 turned these neighbouring countries from uncritical to hostile and left wing. White South Africa felt increasing vulnerable and the government argued that they were now facing a ‘total onslaught’ lead by communists that were intent on bringing them down. The apartheid government reacted to this ‘total onslaught’ with a careful mixture of economic, diplomatic and military foreign policy designed to neutralise the threat by turning these neighbouring countries into political and economic turmoil. South Africa’s proxy war with the rest of the region caused a huge amount of suffering to very many people, especially in Mozambique and Angola.

By the late 1980s the international sanctions were hitting the economy hard.

1.07 History of Violence, Mid1980s

Invention

In the mid-1980s, townships exploded into violence. A ‘them-and-us’ mentality arose. Punishment ‘necklacing’ was invented to target at government informer, sympathiser, or the families of Africans who had taken jobs as administrators or policemen.

Seeds of Crime

Violence became endemic to the townships, and there was a fine line between political violence and general crime. A whole generation of young people missed all their formal involvement in ‘the struggle’ and their chances of employment were extremely remote. Inevitably this fuelled the violence and crime.

1.08 Negotiation and Reformation, Mid1980s onwards

Economic Intention behind Negotiation

In the early 1980s under the presidency of PW Botha, the National Party began to negotiate with the ANC. Business leaders were the first South African establishment figures to talk with the ANC in exile, in September 1985.With sanctions and unrest big business was being squeezed hard and apartheid was no longer making them good profits as it had in 1960s. The business leaders were therefore keen for a political settlement, but were obviously nervous about the intentions of an ANC strongly influenced by communist ideology. The reform seemed impossible after Mandela’s refusal of freedom in exchange of repudiation of the use of violence.

Global Political Climate and Liberation

The collapse of the Soviet block suddenly made ‘total onslaught’ meaningless and the ANC was no longer seen by whites as a frontier for Soviet-backed communist expansion into South Africa.

De Klerk replaced FW Botha and unbanned the ANC. By 1990, nursing South Africa’s crippled economy, de Klerk persuaded the foreign powers to lift sanctions against his country, by withdrawing the army form Angola and Namibia. Mandela and other political leaders were released. The process of negotiating a political settlement got underway.

1.09 Home-made History

Maps

Gauteng, the province Johannesburg is situated, is one of the wealthiest areas in the world, and yet it is dominated by large areas of impoverished townships which until recently did not ‘exist’. Maps of Johannesburg region will not mention Soshanguve, Mamelodi, Tembisa, Daveyton or Carletonville, only Soweto made it to the map, for the reason that Whites will not accidentally enter this zone.

Any description of the South African Landscape that leaves out the impact of humans would not give a visitor any real idea about what the place actually looks like. Apartheid’s legacy is apparent in South Africa’s landscape. The most striking features of apartheid social engineering, such as the huge rural slums that sprang up around the countries, were never shown on official maps.

History Textbooks

During the apartheid era schoolchildren, both black and white were taught a particularly lop-sided version of the country’s history.

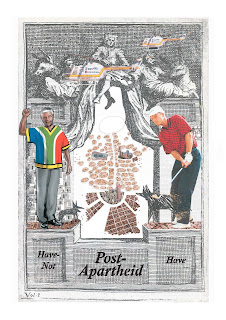

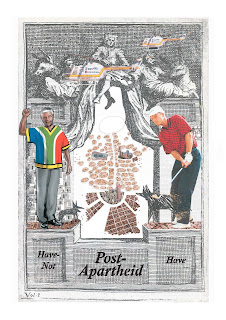

1.10 Political and Racial Upside-Down and Hit-and-Run Urbanization, 1990s

Most of the developments proliferated around 1994 election: threatening of White’s positions in political, social and economic realms. Accompanying with the shakening of White’s status is insecurity of future, increasing crime rate across the city caused exodus of major 1st-World investments.

Now, 1st-world wealth and 3rd-world liveliness are superimposed in downtown, but regarded as invasion of the blacks in the riches’ perceptions. Africans, previously banned from living outside of townships or ‘homelands’, started to move into the rest of the city.

Raw City, 1886

Johannesburg grew up a violent, hard-drinking town servicing tens of thousands of African labourers, skilled white machine operators and entrepreneurs. With very few females, prostitution became the most lucrative industry after mining. Europeans working class girls were cheated and lured to come to Johannesburg and were kept in the brothels as sex slaves. In the early 1890’s a few suburbs, like Parktown and Houghton (5 minutes drive from downtown), had appeared for mining magnates and their families, but the squalid city remained an anarchic place governed by money, greed and raw energy.

Non-violence Campaign

In late 1959 PAC (Pan African Congress, rightist African organization) launched a massive anti-pass law campaign. The pass laws were one of the most hated apartheid policies as they strictly controlled African mobility and were also used by the police as an excuse to stop and search any African.

Their campaign started on 21 March 1960 called on all African men to leave their passes at home and present themselves for arrest at the nearest police station. They believed that the prison could be swamped and the pass laws would have to be revoked. This led to police’s opening fire in Sharpville. Most of the 69 dead and 180 wounded were shot in the back.

As news spread around the country, Africans rioted, went on strike and in Cape Town marched into the city centre. This caused panic amongst the white residents and police. A nationwide state of emergency was declared and the police arrested thousands of political activists from across the country. Strikers were beaten and township food supplies cut off to force people back to work. Both ANC (African National Congress) and PAC were banned. Many of their leaders imprisoned without being charged. Over the next few months the unprecedented harshness of the police action broke the back of the widespread resistance. It also convinced many ANC and PAC members that non-violence action meant nothing if it was met by police brutality.

Armed Attack

ANC established an organised armed wing to carry out sabotage attacks on economic targets, and not to threaten human lives. During an 18 months period from December 1961, 200 attacks were carried out. The activists did attack policemen and collaborators. Its headquarter was discovered at Lilliesleaf Farm in Rivonia. Majority of its leadership, including Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and Govan Mbeki, were arrested and sentenced to life imprisonment.

1.05 History of Violence, 1970s

Continuation of Twisted Darwinism and its Paradox

Forced removal increased as the government set about dividing the country into clear white, Indian, Coloured and African zones. Africans living in cities like Pretoria with ‘homeland’ areas within daily commuting distance (in reality huge distances) found themselves removed to new townships within the ‘homeland’. On occasions the government also altered the borders of ‘homeland’ so that townships on the outskirts of cities were absorbed into a new administrative structure. Forced removals and natural population growth meant that the populations of the ‘homeland’ increased rapidly and though these areas were officially rural their densities were closer to urban areas. All Africans were supposed to express their political rights through the ‘homeland’ administration. During 1970s the South African government encouraged the ‘homeland’ administrations to become independent states. Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana and Venda’s independence were only recognised by South Africa. They do not even recognise one another’s independence.

Bophuthatswana took advantage of its separate status to open casinos- at the time forbidden in South Africa. Sun City, the first large hotel/casino complex, was such a success that it inspired all the other ‘homeland’ governments, as well as those of Lesotho and Swaziland, to open similar enterprises. Sun City is an interesting example of contrast between rich and poor; the gambling rooms and one-armed-bandits operate night and day, while outside the perimeter fence many local Tswana live in terrible poverty. Sun City was upstaged by the even larger Lost City- a transcended Grand Kitsch complex that claims to recreate the atmosphere of King Solomon’s Mines.

Opposition against Oppression

From 1973 on, the Trade Unions, instead of political groups, led successful strikes demanding increased wages. Their strategy was to refuse electing leaders so that the employer had no target and the police could not be called in to arrest strike leaders.

The early 1970s also saw the rise of a more vocal African student protest movement, led by the South Africa Students Organisation (SASO). They rebelled against the mental oppression that taught them white people were somehow innately superior to blacks and an education system designed to make them fit only for un- and semi-skilled occupations. They protested the enforcement of Afrikaans language as a medium of instruction. On the 16 June 1976 a Soweto school pupils’ committee organised a peaceful march, which met with a violent response. The protest ended up as a rampage destroying every symbol of their oppression they could get to, including the government-run beer halls which many pupils felt brought off their fathers’ opposition to state oppression with cheap beer. This event is Soweto Uprising.

The ANC used this new climate of opposition to re-infiltrate South Africa. In the late 1970s they began a new campaign of sabotage with less care to avoid civilian casualties. The ANC released a statement that they were at war with the apartheid state.

1.06 A Vicious Island, 1970s- 1980s

The ANC in exile managed to foster anti-apartheid groups in Europe and North America to put pressure on their governments to institute economic sanctions against South Africa. Most Commonwealth governments supported these sanctions and also instituted sporting and cultural sanctions. This international isolation of Pretoria added to their gradual geopolitical isolation in southern Africa during the 1970s.

The independence of Angola and Mozambique in 1976 and Zimbabwe in 1980 turned these neighbouring countries from uncritical to hostile and left wing. White South Africa felt increasing vulnerable and the government argued that they were now facing a ‘total onslaught’ lead by communists that were intent on bringing them down. The apartheid government reacted to this ‘total onslaught’ with a careful mixture of economic, diplomatic and military foreign policy designed to neutralise the threat by turning these neighbouring countries into political and economic turmoil. South Africa’s proxy war with the rest of the region caused a huge amount of suffering to very many people, especially in Mozambique and Angola.

By the late 1980s the international sanctions were hitting the economy hard.

1.07 History of Violence, Mid1980s

Invention

In the mid-1980s, townships exploded into violence. A ‘them-and-us’ mentality arose. Punishment ‘necklacing’ was invented to target at government informer, sympathiser, or the families of Africans who had taken jobs as administrators or policemen.

Seeds of Crime

Violence became endemic to the townships, and there was a fine line between political violence and general crime. A whole generation of young people missed all their formal involvement in ‘the struggle’ and their chances of employment were extremely remote. Inevitably this fuelled the violence and crime.

1.08 Negotiation and Reformation, Mid1980s onwards

Economic Intention behind Negotiation

In the early 1980s under the presidency of PW Botha, the National Party began to negotiate with the ANC. Business leaders were the first South African establishment figures to talk with the ANC in exile, in September 1985.With sanctions and unrest big business was being squeezed hard and apartheid was no longer making them good profits as it had in 1960s. The business leaders were therefore keen for a political settlement, but were obviously nervous about the intentions of an ANC strongly influenced by communist ideology. The reform seemed impossible after Mandela’s refusal of freedom in exchange of repudiation of the use of violence.

Global Political Climate and Liberation

The collapse of the Soviet block suddenly made ‘total onslaught’ meaningless and the ANC was no longer seen by whites as a frontier for Soviet-backed communist expansion into South Africa.

De Klerk replaced FW Botha and unbanned the ANC. By 1990, nursing South Africa’s crippled economy, de Klerk persuaded the foreign powers to lift sanctions against his country, by withdrawing the army form Angola and Namibia. Mandela and other political leaders were released. The process of negotiating a political settlement got underway.

1.09 Home-made History

Maps

Gauteng, the province Johannesburg is situated, is one of the wealthiest areas in the world, and yet it is dominated by large areas of impoverished townships which until recently did not ‘exist’. Maps of Johannesburg region will not mention Soshanguve, Mamelodi, Tembisa, Daveyton or Carletonville, only Soweto made it to the map, for the reason that Whites will not accidentally enter this zone.

Any description of the South African Landscape that leaves out the impact of humans would not give a visitor any real idea about what the place actually looks like. Apartheid’s legacy is apparent in South Africa’s landscape. The most striking features of apartheid social engineering, such as the huge rural slums that sprang up around the countries, were never shown on official maps.

History Textbooks

During the apartheid era schoolchildren, both black and white were taught a particularly lop-sided version of the country’s history.

1.10 Political and Racial Upside-Down and Hit-and-Run Urbanization, 1990s

Most of the developments proliferated around 1994 election: threatening of White’s positions in political, social and economic realms. Accompanying with the shakening of White’s status is insecurity of future, increasing crime rate across the city caused exodus of major 1st-World investments.

Now, 1st-world wealth and 3rd-world liveliness are superimposed in downtown, but regarded as invasion of the blacks in the riches’ perceptions. Africans, previously banned from living outside of townships or ‘homelands’, started to move into the rest of the city.

Most businesses migrated to northern suburbs of Johannesburg so to be far away from ‘deteriorating’ downtown and Soweto. Within 7 years, a whole new city centre, Sandton, was built in the north: new office blocks, new banking areas, new malls, and new houses……. Blacks’ ‘invasion’ moves towards north, chasing the whites to escape further north, speed of exodus is always caught up by developers. Johannesburg’s sprawl is linking up with Pretoria; the in-between, Midrand, proliferates rapidly. These developments spread unchecked.

Johannesburg after apartheid has the best and the worst of human South Africa: its conflict and creativity, poverty and obscene wealth, open-mindedness and reaction, race hatred and racial mixing, violence and indolent tranquillity, luxury and subsistence, idyll and inferno, excess and need 8, all thrown together into one confused mass driven by money with all the human energy that goes into its pursuit.

PART 2) Post-Apartheid (1994-2001)

2.01 Paranoia Generated Theme Park Urbanism

After smooth political transition, what is generating Johannesburg’s present urbanism is paranoia: fear for losing possessions and fear for violent crime. In the first months of 1996, the murder rate- 30 people killed per 100,000 head of population- was nearly four times of that in the United States.

Theme park is the unconscious architectural strategy; super-reality and ultra-heavenly worlds serve for escaping the real context into an imaginary one. (Projection of Hadrian’s Villa onto urbanism and everybody’s house) Escapism drives the mental picture of the reality into an interface between ‘somewhere else’ and “here and now”. Behind walls, all building typologies are European and historically styled, resurrection of Victorian, Tudor, Mediterranean, Medieval, Georgian themes as backdrops allude to safety and moral correctness through which an unpleasant context can be psychologically denied.

2.02 Paranoia Generated Fortification Urbanism

Speculative development sector completely takes advantage of the situation and launches highly secured “cluster homes” and “office parks”, displaying extreme measures in combating crime.

Characteristics of fortification- mono-functional enclosed zones and inward facing- allow enclaves to be placed anywhere in random without contextual reference. Single-point entry is guarded by private army. Different rules of exclusion and inclusion are applied. Each time one enters a fortified enclave, personal details and motives are recorded.

Public spaces are privatised for exclusive communal use. Enclaves conduct mini apartheid of income classes and mind-sets.

If one house on a street installs an electric fence, the others feel pressured to follow suit, afraid of becoming the most vulnerable property on the block.

Landscape of Surveillance

Behind the high walls and historically styled facades a violent context and insecure future could be denied: walls for segregation, separation and false security. The fortification makes up a landscape of surveillance.

Important items: automatic gates, electrical fencing, spikes, broken glass, razor wire, surveillance camera, immediate armed response from private security army, lighting throughout the property, panic buttons (preferably portable), burglar bars, built-in sirens, dogs (preferably black) etc.

Variations of Walls and Design

Since 1980, security has been the fastest-growing sector in the South African economy, with an annual growth rate of 18 percent. Private security personnel now outnumber the police by two to one. Names like Standby, Fearless, Stallion, Sentry, Peaceforce and Armed Response hint at the services offered by different companies.

Johannesburg after apartheid has the best and the worst of human South Africa: its conflict and creativity, poverty and obscene wealth, open-mindedness and reaction, race hatred and racial mixing, violence and indolent tranquillity, luxury and subsistence, idyll and inferno, excess and need 8, all thrown together into one confused mass driven by money with all the human energy that goes into its pursuit.

PART 2) Post-Apartheid (1994-2001)

2.01 Paranoia Generated Theme Park Urbanism

After smooth political transition, what is generating Johannesburg’s present urbanism is paranoia: fear for losing possessions and fear for violent crime. In the first months of 1996, the murder rate- 30 people killed per 100,000 head of population- was nearly four times of that in the United States.

Theme park is the unconscious architectural strategy; super-reality and ultra-heavenly worlds serve for escaping the real context into an imaginary one. (Projection of Hadrian’s Villa onto urbanism and everybody’s house) Escapism drives the mental picture of the reality into an interface between ‘somewhere else’ and “here and now”. Behind walls, all building typologies are European and historically styled, resurrection of Victorian, Tudor, Mediterranean, Medieval, Georgian themes as backdrops allude to safety and moral correctness through which an unpleasant context can be psychologically denied.

2.02 Paranoia Generated Fortification Urbanism

Speculative development sector completely takes advantage of the situation and launches highly secured “cluster homes” and “office parks”, displaying extreme measures in combating crime.

Characteristics of fortification- mono-functional enclosed zones and inward facing- allow enclaves to be placed anywhere in random without contextual reference. Single-point entry is guarded by private army. Different rules of exclusion and inclusion are applied. Each time one enters a fortified enclave, personal details and motives are recorded.

Public spaces are privatised for exclusive communal use. Enclaves conduct mini apartheid of income classes and mind-sets.

If one house on a street installs an electric fence, the others feel pressured to follow suit, afraid of becoming the most vulnerable property on the block.

Landscape of Surveillance

Behind the high walls and historically styled facades a violent context and insecure future could be denied: walls for segregation, separation and false security. The fortification makes up a landscape of surveillance.

Important items: automatic gates, electrical fencing, spikes, broken glass, razor wire, surveillance camera, immediate armed response from private security army, lighting throughout the property, panic buttons (preferably portable), burglar bars, built-in sirens, dogs (preferably black) etc.

Variations of Walls and Design

Since 1980, security has been the fastest-growing sector in the South African economy, with an annual growth rate of 18 percent. Private security personnel now outnumber the police by two to one. Names like Standby, Fearless, Stallion, Sentry, Peaceforce and Armed Response hint at the services offered by different companies.

Services from security company: immediate armed response, full paramedical back-up services, design and installation of security systems, CCTV and intercom installations, guarding services, 24-hour manned control rooms per region, panic buttons (fixed and portable), attention calls for children alone at home, rendezvous service for unescorted residents returning home, etc: ‘at the touch of a button, the caller’s details are called up and within minutes the good guys are off in pursuit of the baddies.

According to a well-known house and garden magazine, House for Africa, ‘the services of private security company are as essential to a home as its roof, bricks and mortar’, ‘security planning should commence at the design stage of the home and not be added on as an after-thought, security system…be built around the style of the house as well as lifestyle of its residents’.

According to Sentry Security, a popular private army, ‘palisade fencing is an alternative to high walls as it allows residents to observe “in” and “out” of the property. Walls often allow thieves to go about private property undetected, although walls do have the benefit of offering residents privacy’, ‘an alternative to burglar bars is the new type of armoured glass which is bullet-proof and shatterproof, an ideal option for optimal security without building unsightly barriers between yourself and you garden or your view.’

While wealthier inhabitants can afford to install security systems to the perimeters of their property, inhabitants of the townships rely on keeping their front doors shut.

2.03 Lifestyle in Oases

The surrounding geography with little natural beauty to offer (no beach, no mountain, few parks, not even a river), plus the extra violent context, Johannesburg needs extra lifestyle to trap inhabitants from emigration: every house has a lush garden, Bar-B-Q place, swimming pool, some with tennis court and golf course.

The proliferation of cell phones began with the fortified developments, both reflect the fear of crime and display of wealth.

According to a well-known house and garden magazine, House for Africa, ‘the services of private security company are as essential to a home as its roof, bricks and mortar’, ‘security planning should commence at the design stage of the home and not be added on as an after-thought, security system…be built around the style of the house as well as lifestyle of its residents’.

According to Sentry Security, a popular private army, ‘palisade fencing is an alternative to high walls as it allows residents to observe “in” and “out” of the property. Walls often allow thieves to go about private property undetected, although walls do have the benefit of offering residents privacy’, ‘an alternative to burglar bars is the new type of armoured glass which is bullet-proof and shatterproof, an ideal option for optimal security without building unsightly barriers between yourself and you garden or your view.’

While wealthier inhabitants can afford to install security systems to the perimeters of their property, inhabitants of the townships rely on keeping their front doors shut.

2.03 Lifestyle in Oases

The surrounding geography with little natural beauty to offer (no beach, no mountain, few parks, not even a river), plus the extra violent context, Johannesburg needs extra lifestyle to trap inhabitants from emigration: every house has a lush garden, Bar-B-Q place, swimming pool, some with tennis court and golf course.

The proliferation of cell phones began with the fortified developments, both reflect the fear of crime and display of wealth.

Johannesburg bad architecture: it’s so bad, it’s bad vs. Los Angeles bad architecture: it’s so bad, it’s good; mediocre, insecure bad in Johannesburg versus vulgar, sincere, benevolent bad in Los Angeles.

The mediocrity of vulgarity lies in the embarrassment of the riches: political correctness and embarrassed hedonism; you cannot have too much fun when others are still suffering; repressed aggression is expressed in taste in architecture. Their styles reflected the mentality of buyers. One lives in a Mediterranean villa, go shopping in Italian mall, go to work in Tudor Mansion, recreate in ‘Waterfront'.

The bad does not lie in its copy of historical images, its ‘out of place, out of time’ or turning Johannesburg into a giant theme park city of historical and unidentifiably mixed European styles in its architecture, but in the escapist mentality behind it and the manipulation of buyers’ psychological needs.

Walled pleasure zones: Sandton Square- shopping + restaurants + civic centre, ‘Waterfront’ in Randburg (Johannesburg is 6-hour drive from the sea), which is a copy of ‘Waterfront’ in Cape Town, a copy of ‘Waterfront’ in New York.

The mediocrity of vulgarity lies in the embarrassment of the riches: political correctness and embarrassed hedonism; you cannot have too much fun when others are still suffering; repressed aggression is expressed in taste in architecture. Their styles reflected the mentality of buyers. One lives in a Mediterranean villa, go shopping in Italian mall, go to work in Tudor Mansion, recreate in ‘Waterfront'.

The bad does not lie in its copy of historical images, its ‘out of place, out of time’ or turning Johannesburg into a giant theme park city of historical and unidentifiably mixed European styles in its architecture, but in the escapist mentality behind it and the manipulation of buyers’ psychological needs.

Walled pleasure zones: Sandton Square- shopping + restaurants + civic centre, ‘Waterfront’ in Randburg (Johannesburg is 6-hour drive from the sea), which is a copy of ‘Waterfront’ in Cape Town, a copy of ‘Waterfront’ in New York.

2.04 Towards a Middle Class Society?

Society is emerging into a middleclass one. Could the evening-out process lead to homogenisation? People are aspired to a, at least, middleclass lifestyle. Extreme contrast will start disappearing. Contrast of weekday and weekend, hardship and reward, pleasure and labour will also be levelled. (anaesthetic, numb) Then, the desire to escape from daily routine and daily pleasure (normality, the norm, the monotone of life) will become even stronger. People will need more escape and ecstasy then.

2.05 The Beauty of Paranoia

Beauty of life is inspired and squeezed out from the paranoia. Living in Johannesburg is the most thrilling urban experience.

Private possession of weapons inspires the never-ending cop-and-thieve game - wild, wild south – people take pleasure joining in neighbours and friends’ hunt for the baddies.

In individual’s private life- extreme hedonism and weird fun- one does not know about tomorrow so enjoy now.

Animal game farm – shooting and killing wild animals in the bushes- to release aggression and frustration from urban life.

Sun City/Lost City and many other in-the-middle-of-nowhere pleasure zones are little Nevada’s in Southern Africa.

Society is emerging into a middleclass one. Could the evening-out process lead to homogenisation? People are aspired to a, at least, middleclass lifestyle. Extreme contrast will start disappearing. Contrast of weekday and weekend, hardship and reward, pleasure and labour will also be levelled. (anaesthetic, numb) Then, the desire to escape from daily routine and daily pleasure (normality, the norm, the monotone of life) will become even stronger. People will need more escape and ecstasy then.

2.05 The Beauty of Paranoia

Beauty of life is inspired and squeezed out from the paranoia. Living in Johannesburg is the most thrilling urban experience.

Private possession of weapons inspires the never-ending cop-and-thieve game - wild, wild south – people take pleasure joining in neighbours and friends’ hunt for the baddies.

In individual’s private life- extreme hedonism and weird fun- one does not know about tomorrow so enjoy now.

Animal game farm – shooting and killing wild animals in the bushes- to release aggression and frustration from urban life.

Sun City/Lost City and many other in-the-middle-of-nowhere pleasure zones are little Nevada’s in Southern Africa.

New obligation: to be politically (hence racially) correct, rules of exclusion and inclusion needs to be strategised in more inventive, absurd and sick ways.

Complete mobility: total proliferation of cars and cell phones. Consequence of mobility: delocation whatever population, business or industry. Source of violence being speed (some fast forward, some left behind), exclusion, incarceration (imprisonment), collision, ghettorisation, alienation, lack of rights (some people fell out of communal life into unmediated life), xenophobia (fear of foreigners/strangers).

Can we imagine a South Africa without walls and full of pleasure? Or with walls and full of pleasure? Without fear and paranoia, none makes sense. (Johannesburg is largely supported by and constructed out of paranoia; some people live off the thrill of paranoia.)

2.06 Future???

Imaginary enemy

Future has to be addressed from the present. The present situation has to be reinforced and enhanced to deal with the perpetual paranoid mentality embedded in the society.

Assumptions

1) Johannesburg doesn’t make sense without paranoia and prejudice (in fact no where exist non-prejudice and non-discrimination)

2) For Johannesburger, the only way to enjoy life in the city is to believe that they are threatened by crime, the bad guys and the inhabitants form the other side

Complete mobility: total proliferation of cars and cell phones. Consequence of mobility: delocation whatever population, business or industry. Source of violence being speed (some fast forward, some left behind), exclusion, incarceration (imprisonment), collision, ghettorisation, alienation, lack of rights (some people fell out of communal life into unmediated life), xenophobia (fear of foreigners/strangers).

Can we imagine a South Africa without walls and full of pleasure? Or with walls and full of pleasure? Without fear and paranoia, none makes sense. (Johannesburg is largely supported by and constructed out of paranoia; some people live off the thrill of paranoia.)

2.06 Future???

Imaginary enemy

Future has to be addressed from the present. The present situation has to be reinforced and enhanced to deal with the perpetual paranoid mentality embedded in the society.

Assumptions

1) Johannesburg doesn’t make sense without paranoia and prejudice (in fact no where exist non-prejudice and non-discrimination)

2) For Johannesburger, the only way to enjoy life in the city is to believe that they are threatened by crime, the bad guys and the inhabitants form the other side

New typology

How to come up with new typologies that deal with the mentality but protect natural landscape and the innocent (those who are not responsible but are blamed for, including people and animals)? What could be the therapy for a healthier future? And how to control sprawl?

Zoos might have to be more than zoos (so new typology of zoo living- exhibitionism); prisons have to become more than prisons (so new typology of prison-claustrophobia), they will be super zoo living and super prison living.

How to turn banal in to beauty, ordinary into poetry (to inverse and to turn upside down)? The wall has to be penetrated for the opposite systems to start communication and flow freely from one side to the other.

Research Material

Postcards

Advertising pamphlets picked up at traffic intersections

Visiting house-sell show

Local home and garden magazines

Snap shots and videos

Ariel photos

Film: Joburg Stories

Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic (1998). Blank- Architecture, apartheid and after. Nai Publishers, Rotterdam.

Mike Davis (1998). City of Quartz- Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Chapter 4: Fortress L. A., pg 223-263. Pimlico, London.

Mike Davis (1998). Ecology of Fear- Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, Chapter: Beyond Blad Runner, pg 359-422. metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York.

Sebastian Ballard (1998). South Africa-Handbook. Footprint Handbooks, Bath.

How to come up with new typologies that deal with the mentality but protect natural landscape and the innocent (those who are not responsible but are blamed for, including people and animals)? What could be the therapy for a healthier future? And how to control sprawl?

Zoos might have to be more than zoos (so new typology of zoo living- exhibitionism); prisons have to become more than prisons (so new typology of prison-claustrophobia), they will be super zoo living and super prison living.

How to turn banal in to beauty, ordinary into poetry (to inverse and to turn upside down)? The wall has to be penetrated for the opposite systems to start communication and flow freely from one side to the other.

Research Material

Postcards

Advertising pamphlets picked up at traffic intersections

Visiting house-sell show

Local home and garden magazines

Snap shots and videos

Ariel photos

Film: Joburg Stories

Hilton Judin and Ivan Vladislavic (1998). Blank- Architecture, apartheid and after. Nai Publishers, Rotterdam.

Mike Davis (1998). City of Quartz- Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, Chapter 4: Fortress L. A., pg 223-263. Pimlico, London.

Mike Davis (1998). Ecology of Fear- Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, Chapter: Beyond Blad Runner, pg 359-422. metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, New York.

Sebastian Ballard (1998). South Africa-Handbook. Footprint Handbooks, Bath.